|

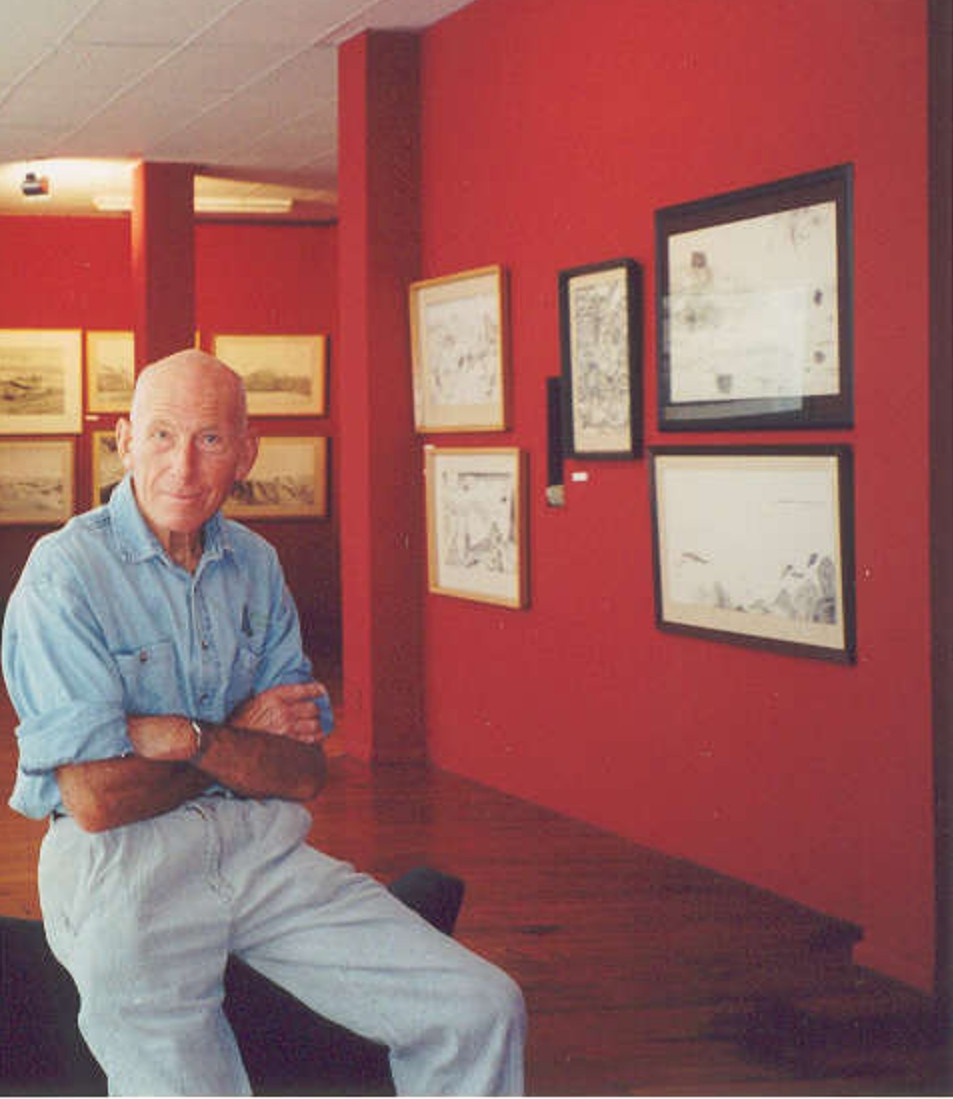

David Cheer was a self-taught artist who began drawing in the early 1950s. Working primarily on paper with conte, pencil and charcoal, his art most commonly dealt with landscape but frequently introduced fantasy, abstract, historical and war themes.

Generally rendered in dark, fluid, atmospheric detail, his subject matter was drawn from an eclectic range of interests – reflecting among other things his childhood in the central North Island backblocks, the interplay between Canterbury's weather and landforms, a subtle understanding of the relationship between psychology and mythology, an enduring fascination with the air battles of World War Two, sailing ships, stellar geology and his extensive, diverse, well-studied book collection.

Likened throughout his career to Blake, Durer, Piranesi, Goya and Rouault, critics appraising David Cheer's draughtsmanship frequently used expressions relating to honesty, clarity, vision and perception while commenting on his vigour, spontaneity, masculinity and restless energy.

Pieces exhibited at The Arthouse Gallery in Christchurch (September and October 2010) were completed between 2006 and 2008 and reflected a move into figurative work hitherto unexplored.

As much an exercise in emotional perspective and placement as a test of his ability to draw the human figure, the series was challenging to the viewer and also played a few tricks.

The classical themes of Greek nymphs and ancient ruins were joined by tall ships (the biggest ever built); World War Two fighter planes, astral plains and sweeping landscapes – unnamed and anonymous, but so familiar to New Zealanders. Almost all works included the diverse observational gaze of a figure or two.

His work features in five public collections throughout the country, including the Robert MacDougall Gallery and the Hocken Library and in private collections such as that accrued by Sir Bob Jones. Since 1963 he exhibited in all major centres and in 1973 was guest exhibitor with The Group, which included such names as Hotere, McCahon, Woollaston, Trusttum and Wong. David Cheer will also be known to readers of literary publications such as Landfall, Ascent and Islands, where his art has been frequently reproduced. He exhibited frequently in the 1970's and 80's and his last exhibitions were in 2001 and 2010 at CoCa, Selwyn Gallery and The Arthouse.

Born at Bells Junction, Rangitikei in 1931, he spent his entire artistic career in Canterbury, supporting himself and his family through work as a carpenter. His additional interests included writing (essays and short stories published), reading and collecting books (over 6,000 volumes), riding motor bikes and watching independent international films (he was a past-President of the Canterbury Film Society). He died in Christchurch in 2012 and is survived by his three daughters.

Ray Grover, a former NZ national archivist, is a published fiction and non-fiction author and was a lifelong friend of David Cheer. This essay was originally written as part of the catalogue for David Cheer's 1973 exhibition at the Canterbury Society of Arts in Christchurch.

David Cheer has been drawing pictures since he came to Christchurch in the

early

1950s. Expressing a vision that has been conceived in solitude and which is

aggressive to any threat to its independence, it was probably inevitable that

it would take many years before there was even a degree of public recognition

of his achievement. Entirely self taught he owes nothing to any art school.

Neither has he tagged along after current international modes. The links he has

are with those Europeans of the past who expressed their vision in line—a

vision that is seen at its greatest in the etchings of Piranesi, the drawings

of Goya, and the pictorial works of Blake. In New Zealand his landscapes have

similarities with Buchanan's Milford Sound and Heaphy's

Mount Egmont.

David

Cheer works in pencil and he is a master of the medium. The viewer is

constantly surprised by the versatility of his use of it. Slender threads rise

like the tendrils of a rock pool plant, a few carefully placed strokes make a

blank page into a snow field, and a dense blackness is a mass in one picture

and a void in another.

He

rarely attempts to woo or charm his viewers. His statements are curt and

uncompromising. Often enigmatic, they require that we exercise our perception

on them over a period of time before we begin to discern what he is about.

There

is a masculine toughness that we tend to associate with those who fought at

Monte Cassino or who settled the central North Island

where he grew up and which he frequently draws. When he depicts a landscape his

scenes are as verifiable as those in the topographical photographs he uses as

preliminary recording sketches. On superficial examination the pictures might

appear to be little more than examples of first rate draftsmanship but if the

viewer allows himself to ponder on what he sees he will become aware that the

combination of craft and imagination transforms the photographic images into

strange and disconcerting metaphors.

A

prospect of hills broken in for farming is a vast flayed carcass, an

overhanging cloud bank deliberately advances as an enveloping menace, and a

weathered mountain, its sleet-covered rock face meticulously drawn, becomes a

dour Prometheus. His imagination also responds to phenomena beyond this world

and we find ourselves confronted with the vastness of the Milky Way and the

cosmic terror of a supernova explosion.

The

forms in his most successful abstract pictures share the same basic qualities

of those found in his other works in that they are topographical, climatic, and

astronomical forms reduced to their essence. In these pictures a pattern of

hard black lines follows the same rhythm as a landscape of ridges. In another a

pale asymmetrical cone licking upwards into a void is seen to have similarities

with a sun flare. The common source of the forms he uses becomes especially

evident in those pictures in which he combines the abstract and the actual.

These are amongst his most dramatic works.

His

pictures may sometimes be still but they are never static. There is one called 'Forest' which has grass in the foreground, a beech forest

with a peak rising behind it in the middle, and a background of mist. The mist

obscures part of the peak. The lines are softer than usual and it is the

nearest I have seen David Cheer come to depicting a conventional landscape of

romantic tranquillity. What prevents it from being so

is the mist. Looking at it we know that the mountain and the bush will soon be

swept by a snowstorm.

There

is a tension in all of his pictures, the tension of opposing forces. When the

eyes come to rest on one object they soon find that they are being made to look

at another which has been placed counter to it. At other times they find

themselves moved because the point on which they have fixed is not a discrete

unit but is part of a continuum and they are soon gliding along from one line

to another like a train being switched through a marshaling yard.

The

district where David Cheer was born and raised is just south of Ruapehu in the hill country that extends from Rangitikei to

Northern Taranaki. This country has been washed into

a tangle of ridges and valleys by a multitude of rivers and streams. At one

time it must have been flat because the summits of the hills rise to a pretty

consistent thousand feet. When you see before you the jumble of ridges and

gullies and the uniform height of the summits the vista seems to have no end.

The feeling of infinity is further enhanced by the nature of the horizon. Perhaps

it is because of the serrations visible even on the farthest ridges, but it

appears that earth and sky do not meet but extend onwards together.

If

ever there was an environment that would encourage a boy to feel that he

existed in an infinite universe, it is this one. Even the bulk of Ruapehu would not set a limit as the forces that thrust it

up would be seen as a defiance of the infinite rather than a denial of it.

David

Cheer is essentially a visionary artist. From an early age it was impressed on

his imagination that the true reality was to be found in the infinity and

forces of the universe. The key to it would be his imagination and the only

limitations would be those that existed in himself. As

a visionary he would seek to go beyond the reality that was immediately apparent to his senses. But he would not reject this

reality: he knew it contained its own transcendence.

"...magnificently harmonious sense of balance and tranquillity that has to do with the essence of being."

Riemke Ensing, Sunday Star,

2-6-91

"...suggests a reconciliation between the dark, and

seemingly diametric, outer provinces of what is generally perceived to be

reality."

Peter Ireland, Art New Zealand, Autumn 1987

"Action-packed

is the best way to describe Cheer's drawing. There is

nothing passive about his viewpoint or way of working."

John Coley,

Christchurch Star, 1-7-81

"...continually delights because, while his drawings are

instantly recognisable, each blazes his trail a

little further."

John Summers, The Press, 26-4-77

" ...has proved many times that the most humble medium, a

pencil, in the hands of a man with a probing mind and something to say, can be

more effective than any amount of new media."

GT Mofitt,

The Press 9-3-69

" ...the subject seems divorced from straight documentation and

one feels that the artist has isolated a telling fragment of his imagination."

Quentin MacFarlane, The Press 22-5-68

"It

is a difficult art which can be felt rather than explained: art of the mind

which requires the closest study if one is to get the message. And it is well

worth the effort."

John Oakley, Christchurch Star, 20-5-68

|

|